What’s that? You never knew there was a connection between the two topics? (Neither did I, I must admit.) Ah, let us read and learn, Grasshopper. Alice Duer Miller figured out the relationship a century ago.

|

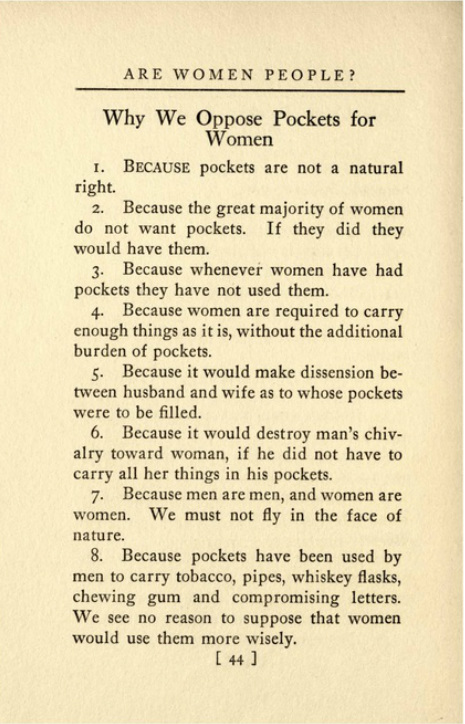

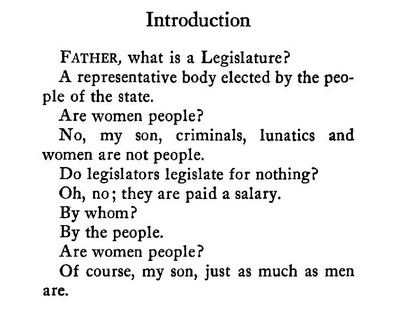

Are Women People? includes a number of list poems, modeled after oft-repeated arguments against woman suffrage, such as this one from the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. I’d be hard-pressed to pick a favorite list poem from Alice Duer Miller's book -- I love them all, and as I mentioned in my last post, I’ve got a bit of a writer's crush on her. But since April 21 is Poem in Your Pocket Day, my choice for this post is easy -- a list poem about pockets and women’s suffrage. What’s that? You never knew there was a connection between the two topics? (Neither did I, I must admit.) Ah, let us read and learn, Grasshopper. Alice Duer Miller figured out the relationship a century ago. Respond with a comment below, and I’ll pick one person at random to receive a copy of my latest book, Presidential Politics by the Numbers. Enter by April 30; I’ll draw for the winner on May 1. If you include a suffrage list poem of your own à la "Why We Oppose Pockets for Women," I'll give you a bonus entry. I’d love to see an entire poem, but I’ll settle for a couple of items.

4 Comments

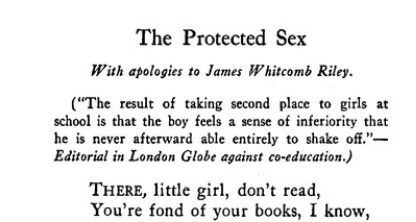

When someone mentions a 19th or 20th century suffragist, do you conjure up an image something like this? Stuffy maiden aunts with a bun of gray hair – no ears showing – who had sworn a solemn oath* to never smile or – gasp – laugh until women got the vote. Think of the pictures you’ve seen of the venerable and supreme suffrage leader, Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906). She starting campaigning for suffrage in her early 30s and kept it up for more than half a century -- and still didn't get to see success in her lifetime. She famously said "failure is impossible," but, yikes, what a long slog. I suspect a photo of a smiling SBA is about as likely to surface as a bottle of hooch at a 19th century temperance meeting. Other suffragists don’t exactly appear to be a laugh a minute, either. Of course, I realize this quirk isn’t attributable to suffrage, but rather the photography practices of the day.** Another contributing factor – it seems that many of the most familiar photos show leaders in their later years, further lending a serious note, in my opinion. (I’m not exactly a young pup, so I think I can safely say that.) Anyway, I believe these photos and the very serious cause suffragists fought for could cause reasonable people to conclude that humor was perennially absent. But then along comes Alice Duer Miller to destroy that stereotype of dour suffragists. The multi-talented Duer Miller wrote verse for the New York Tribune in a column called Are Women People? Many of these columns were reprinted in her 1915 book with the same title. It took me forever to write this short blog post because, I'll admit, I went all fan-girl when I discovered Duer Miller and her pro-suffrage/feminist poetry. I definitely kept going down one rabbit hole or another in search of more info. Since this is National Poetry Month, I’ll aim to share more of her verse and her life in the next few weeks. (I'm really looking forward to Poem in Your Pocket Day -- April 21.) Here are a couple of selections from Are Women People? to get things rolling. This little ditty is from pages 34-35. See *** below to find out why she's apologizing to a fellow poet. So, am I the only one who is captivated by Duer Miller’s writing? Are you surprised that humor had a place in the suffrage movement? ***********

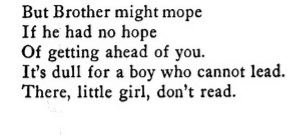

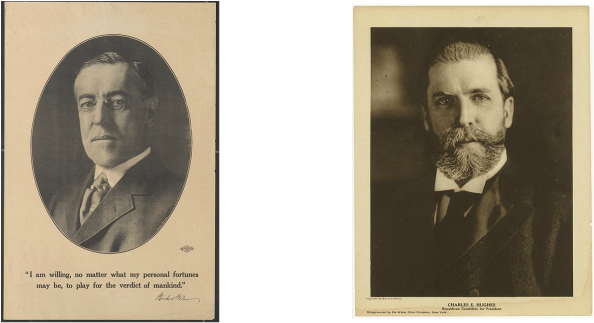

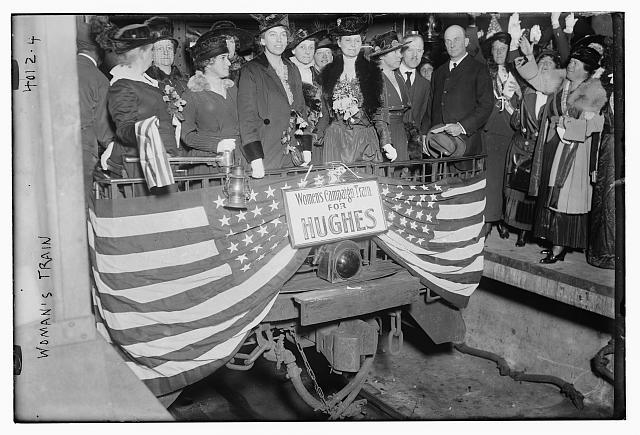

*Many early suffragists, including Susan B. Anthony, were Quakers, and Quakers were opposed to oath-swearing, so maybe they came up with a clever alternative? **The lack of smiling faces old photographs isn't merely because of lengthy exposure requirements. Check out this Smithsonian video and this Guardian article for some context. ***Often referred to as the “The Hoosier Poet” or the “The Children’s Poet,” James Whitcomb Riley was famous in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Here Duer Miller is riffing on his poem, A Life-Lesson, which begins with these lines: There! little girl; don't cry! They have broken your doll, I know … Running for president in 1916: Democrat and incumbent Woodrow Wilson vs. Charles Evans Hughes, former Supreme Court justice and Republican. Who could vote in 1916? White males of all sorts -- requirements that they had to be property owners had long been banished. Males of color? Supposedly they could vote. The 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, said so, after all. However, decades later, true suffrage remained a chimera for most non-whites. And what of women? Some could legally vote, but most could not. It came down to geography. I got to thinking about this the day of the Illinois primary a few weeks ago. My eldest daughter in Chicago faced a daunting to-do list, including driving seven hours for an audition, yet she was adamant about voting before her trip. Inspired, I decided to do some time travel and examine the question based on her location, that of my other two-college-age daughters (Minnesota and Iowa), and mine (South Dakota). In 1916, the 19th Amendment's guarantee of suffrage for women was still four years away. Both figuratively and literally, a lot of bloodshed was yet to come in suffrage skirmishes and on World War I battlefields. (The war played a significant role in advancing woman suffrage, as it was typically called.) Nevertheless, by 1916, several western states and one state east of the Mississippi allowed women to vote -- specifically, the right to vote for president, as women in some states had partial suffrage rights. A century ago, suffragists couldn’t get behind Wilson's reelection campaign. His stance on woman suffrage was -- how shall I describe it? -- fluid. His suffrage phases encompassed the following (please permit me some leeway with the paraphrasing):

[What’s that, you ask? Did Wilson experience a true conversion or simply bow to political expediency? Good question.] Anyway, in 1916, President Wilson was still firmly outside of the pro-suffrage amendment camp as he campaigned for re-election. The official party platform purported to support woman suffrage, as long as it happened on a state-by-state basis. The Republican platform said the same, albeit in more flowery language. All I can say is that it’s a good thing women didn’t wait around for state-by-state suffrage, or some of us might still be disenfranchised today. In 1916, the quest for woman suffrage looked a lot like the proverbial tortoise and hare race – but stuck at the part where the tortoise looked to be the likely loser. By then, the battle for the ballot box was nigh on 70 years old. The tortoises/suffragists seemed to get a boost when candidate Evans ventured beyond the official party platform and backed a federal amendment: “I think it to be most desirable that the question of woman suffrage should be settled promptly … for the entire country. My view is that the proposed amendment should be submitted and ratified and the subject removed from political discussion.” (From The New York Times, August 2, 1916.) Charles Evans Hughes – it sounds downright presidential, doesn’t it? Alack and alas … (although truth be told, I don’t know much about Hughes beyond what I’ve told you here).

Wilson’s campaign slogan was “He kept us out of war” (phrased, as you notice, in the past tense, and one that remained true only until April 1917). Wilson prevailed in the general election – but barely – with a margin of less than 600,000 in the popular vote and just 23 in the Electoral College (277 to 254). To get back to my original question: My 21-year-old daughters and I, in South Dakota, Minnesota, and Iowa, would have been voiceless on November 7, 1916. I suppose we’d have had to hope that my husband/their dad voted as we would have. One vote on behalf of four of us -- and no room for differing opinions, apparently. My eldest, in Illinois, would have had the rare honor of voting. That's because in 1913, Illinois became the first state east of the Mississippi to allow women to vote for presidential electors. Allow me a short digression (again). Ironically, Illinois women could vote for president in 1916 but weren’t allowed to vote for governor and some other elected offices. And, to minimize the risk of cooties, they had to use separate ballots and ballot boxes, according to author and historian Mark Sorensen. Okay, I made up the part about cooties, but I didn’t make up the part about separate ballot boxes. (Sorensen’s brief history of woman suffrage in Illinois makes for good reading.) So, when could women vote in your home state, territory, or country? Check out this map for further info for the U.S. And how would you have voted 100 years ago? |

Mary Hertz Scarbrough

Join me as I share some lesser-known stories from the annals of women's suffrage and other topics. Look for some useful research tips from time to time as well. Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed